How does a pandemic affect an economy? Obviously, it’s a multilayered topic and FRED has limits to what it can reveal. The good news, of course, is that large-scale pandemics are rare. So the economic effects for most of these outbreaks are hard to see by graphing data. But we can take two of the most extreme examples, which will have visible effects in the data: the Black Death of the mid 14th century and the Spanish flu of 1918-1920.

We already covered the first one in a post from December 2018. So we look at the second one today: the influenza outbreak of 1918, commonly known as the Spanish flu. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, this pandemic infected about a third of the world’s population and killed at least 50 million people.

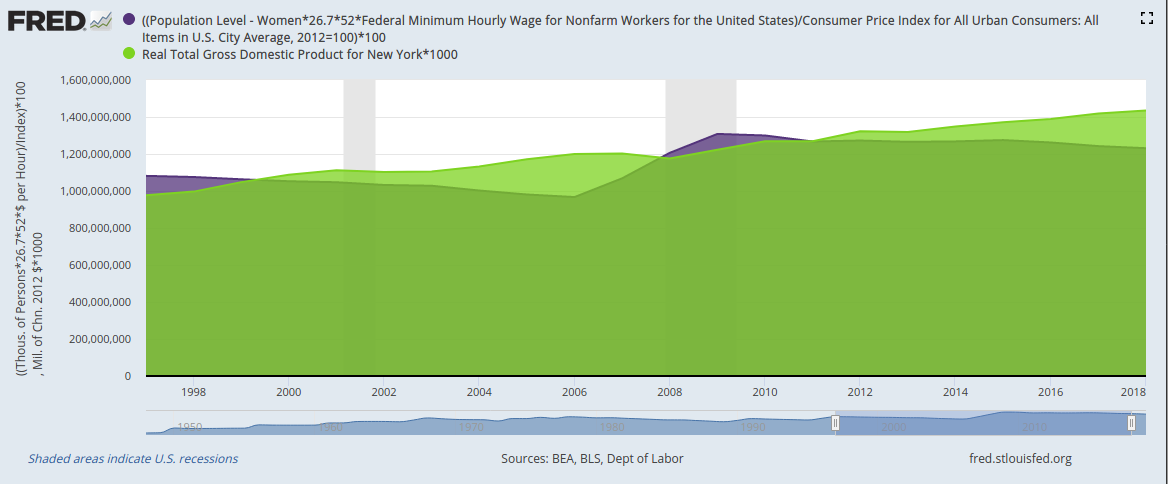

So, what economic effects can we see? The graph above shows hourly wages for various trades in the United States, and one particular feature of the data is a run-up of wages from 1918 to 1920 (followed by a drop, with the recession of 1921). This effect is consistent with the economic theory behind a sudden loss of population, just as we showed for the Black Death.

In the case of the Spanish flu, we also need to disentangle it from the consequences of World War I. Luckily, there’s some additional analysis in a St. Louis Fed Review article and other work by Thomas Garrett. Indeed, not all U.S. cities were affected in the same way by the Spanish flu or by WWI casualties. Exploring these differences, Garrett shows that the effect of the Spanish flu on wages was real and even bigger than the effects of WWI.

How this graph was created: Search for “Average Hourly Money Earnings” and click on one of the relevant series. From the “Edit Graph” panel, open the “Add Line” tab and search for more series. Repeat as needed.

Suggested by Christian Zimmermann.